“I think it was pretty cool,” said Travis Perry, a jovial, burly barber who was working the day Emhoff visited the shop. “I’m glad he came.”

Did it make him rethink his decision not to get the Covid-19 vaccine?

“No way,” Perry deadpanned.

The person sitting in Perry’s barber chair chimed in.

“Ain’t nothing going to make me take that unless my life is on the line,” C.J. Ayers said of the vaccine. “The CDC barely knows about the disease, y’all trying to tell me about a vaccine y’all just threw together in a month? Nah. I’m not doing that.”

What about the hundreds of millions of people who already got the vaccine and are all OK?

Ayers didn’t skip a beat: “I ain’t got it and I’m OK too.”

The skepticism repeated again and again with customers at It’s Official Barbershop, reflects a broader sentiment shared by people throughout Englewood, a predominantly Black neighborhood that also has one of the highest crime rates in Chicago. Just 28 percent of those living in the 60621 zip code, which includes much of Englewood, have been fully vaccinated and only 33 percent have received one dose, according to city of Chicago statistics. It’s one of the lowest vaccination rates in the country.

It’s also a microcosm of the obstacles facing the White House nationwide. For all the celebrity plugs, offers of free beer, and cash lotteries, the national vaccination push is hitting a brick wall of reality. Conspiracies, lethargy and a sense that the pandemic is on the wane have intervened as the demand for the vaccine has dropped nationally from 2 million shots per day in early May to closer to 1 million per day by mid-June.

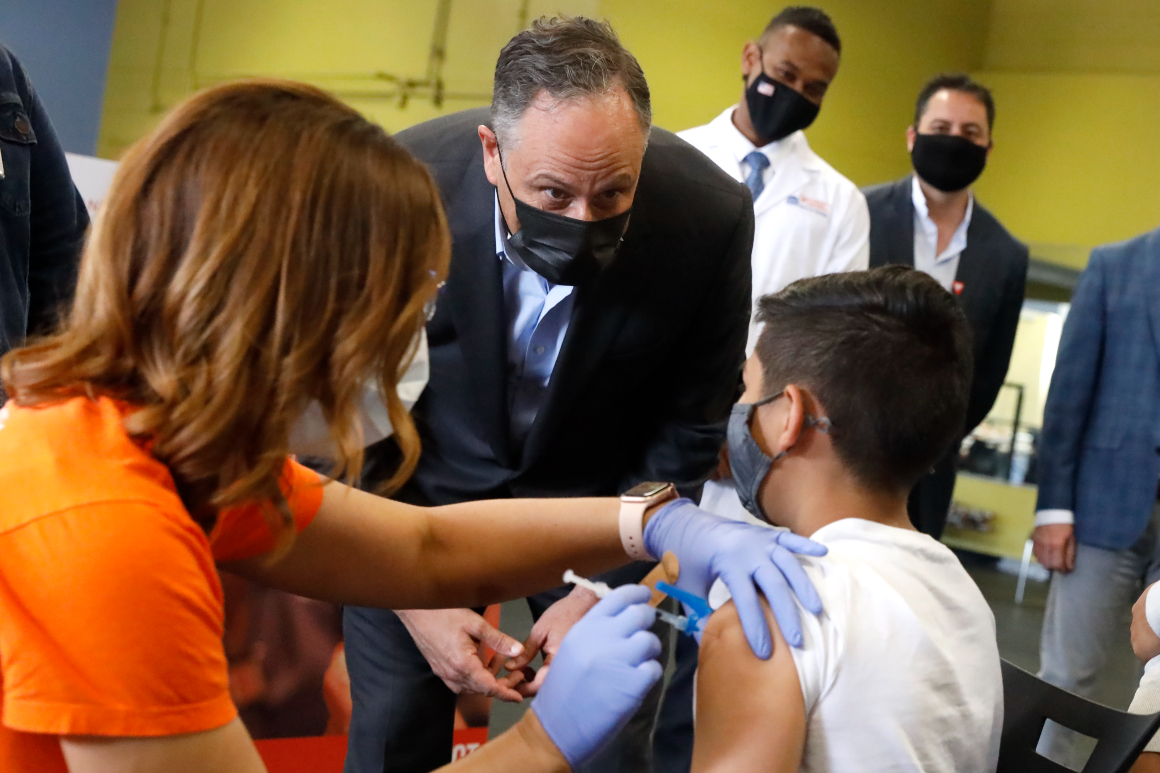

After falling short of its goal of administering at least one dose of the vaccine to 70 percent of adults by July 4th (it reached 67 percent) the White House is now turning its attention to the toughest populations in the country. That includes places like barber shops in Englewood, which are part of the “Shots at the Shops” effort by the White House. It’s also sending “surge teams” to some of the lowest vaccinated spots in the country, enlisting trusted messengers like church leaders to go door-to-door. And they’ll add mobile vaccination units at places like music festivals, sporting events or neighborhoods with low vaccination rates.

“Now we need to go to community-by-community, neighborhood-by-neighborhood, and oftentimes, door to door — literally knocking on doors — to get help to the remaining people,” President Joe Biden said in an address on vaccinations Tuesday.

It’s all in an effort to target the stubbornly resistant, or hard-to-reach populations as fear grows that the virus could reemerge thanks to the highly contagious Delta variant.

Much of the coverage of those populations has focused on Trump supporters who have resisted vaccination as a matter of political identity. And data show that vaccination rates do tend to overlap with partisan leanings. But there are other hard-to-reach communities, including young people, Black and minority groups that traditionally vote Democratic.

“We’re no longer in the days where 6,000 people are getting vaccinated. If 12 people are getting vaccinated in the barbershop on a Saturday morning — that’s a big deal,” said Dr. Cameron Webb, senior policy adviser for equity on the White House Covid-19 response team. “And we think that that kind of person-to-person, real hand-to-hand work of continuing to reach more people, that’s what this phase of the vaccine effort is going to look like.”

At the “It’s Official Barbershop,” the obstacles to the vaccine run much deeper than mere apprehension. The scourge of gun violence has consumed the lives of Englewood residents, as it has in other predominantly Black and brown neighborhoods of Chicago. With nearly 300 homicides since January, and already more than 1,500 shootings, the city is facing one of the bloodiest summers in recent history.

Anecdotally, customers grimly admit they’re used to the persistent violence, but this year, they’re startled by what seems like younger shooting victims. While the White House has said it would work with officials in Chicago, among other big cities, to combat the flow of weapons, the talk here is of a lack of real economic opportunities — good-paying jobs that earn more than just minimum wage — more youth programs and confronting drug dealing.